For my first 6 months as a contractor at Government Digital Service I worked on the transition tools team as a frontend developer, designer and user researcher. We were building the tools needed to transition 800 government department and agency websites to GOV.UK. All 24 ministerial departments had already been migrated. In October 2013, transition was in full swing and it was a complex process.

No link left behind

A principle of transition is no link left behind, as Sir Tim Berners-Lee explains: cool URLs don’t change. Paul Downey says:

URLs - links and Web addresses - are the ‘strands’ in the Web metaphor. When URLs change, the strands break.

All government content is moving to GOV.UK, the old sites are being retired. That’s the potential for a lot of broken links. Across 800 websites there are over 1 million unique URLs. Government has lots of links in the wild; on websites, but also in letters, on mugs, in ads and on TV. Users will continue to click and type these URLs, expecting to reach the content they need. Those old URLs must continue to meet that need. Government needed a way to manage these URLs.

Managing mappings with the transition tool

Every old URL has a mapping from old to new. These are managed in a rails app named Transition.

An old URL can:

- be redirected to a GOV.UK page

- be archived

Redirects (301)

Redirects are served with a 301 status code, a permanent redirect. For example, this page on the old Environment Agency was for checking your flood risk:

http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/homeandleisure/floods/31644.aspx

It redirects to the equivalent content on GOV.UK:

https://www.gov.uk/check-flood-risk

Archives (410)

Not all roads lead to GOV.UK. Archives are for content that doesn’t meet a user need. Content without a need isn’t transitioned to GOV.UK. These old URLs display a notice and a link to a version of the page on the National Archives.

For example this page about the old DFID website’s cookie policy is archived, with a link to the archived version:

http://www.dfid.gov.uk/about-dfid/privacy-and-cookies

They’re served with a 410 status code. 410 means “Gone”:

The requested resource is no longer available at the server and no forwarding address is known. This condition is expected to be considered permanent.

Research and design

From the first prototype to the live application we conducted frequent user research sessions with our government users. Research asked users to perform tasks and probed their understanding of the process. These sessions led to iterative changes in the application, changes that were tested again with further research, either validating our patterns or challenging our assumptions.

Words not status codes

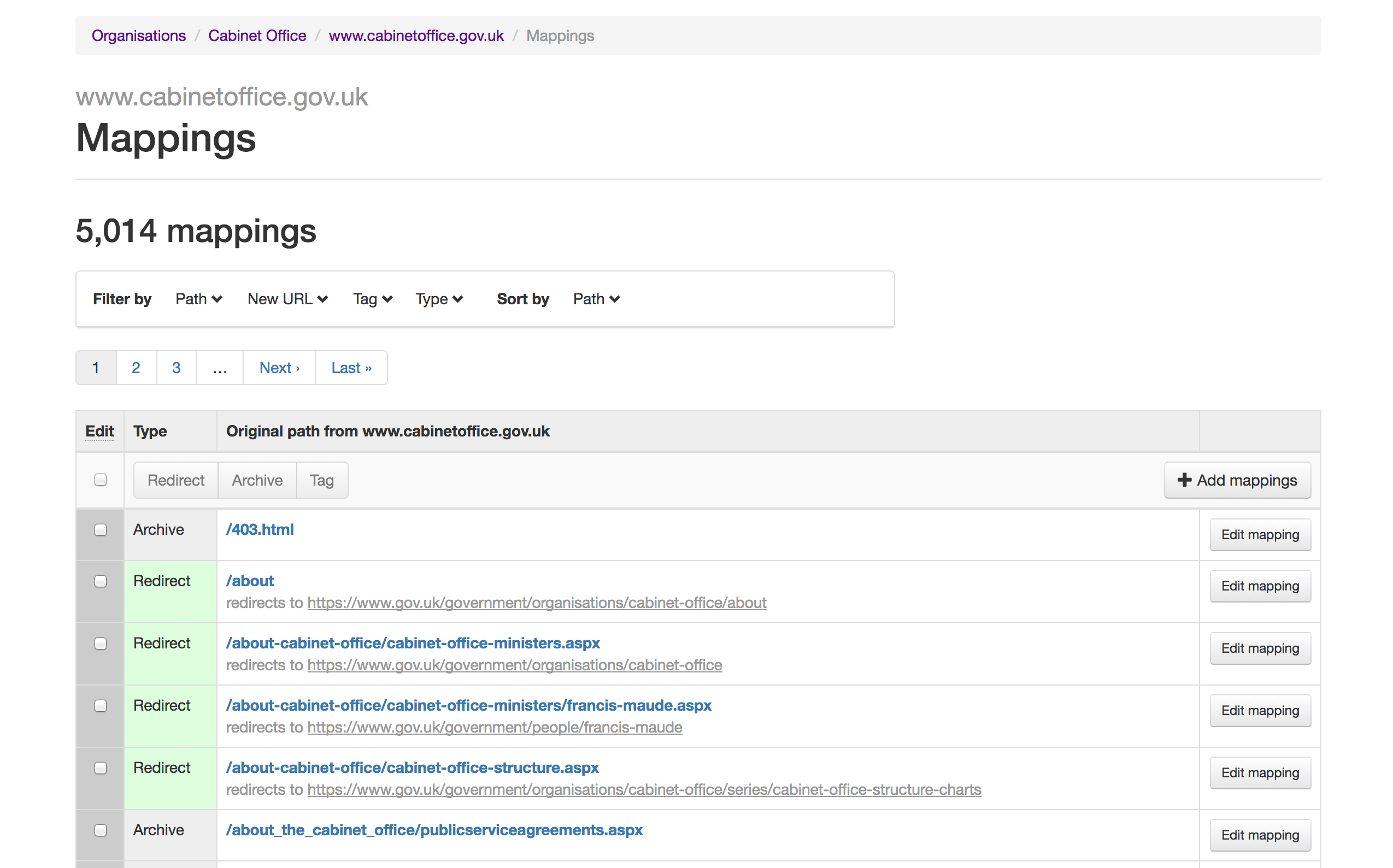

An early version of the application used 410, 404 and 301 for mappings. Research showed that users didn’t know what these codes meant, or worse, interpreted them wrongly. Rather than explaining the codes we replaced references to them with “Redirect” and “Archive”, terms users knew already, titling them with “Type” rather than code.

Handling many paths

Managing thousands of mappings is a daunting task. Editing them one by one was very obviously not ideal, creating bulk editing tools was a big deal.

Research highlighted that:

- many similar paths get redirected to the same GOV.UK page

- many similar paths get archived

- sites without a clear URL structure were harder to manage

- users needed to group paths to manage them

- groups used for paths would be dependent on website and organisation

- it was hard to know which paths were most important

- it was unclear which paths had already been checked or edited

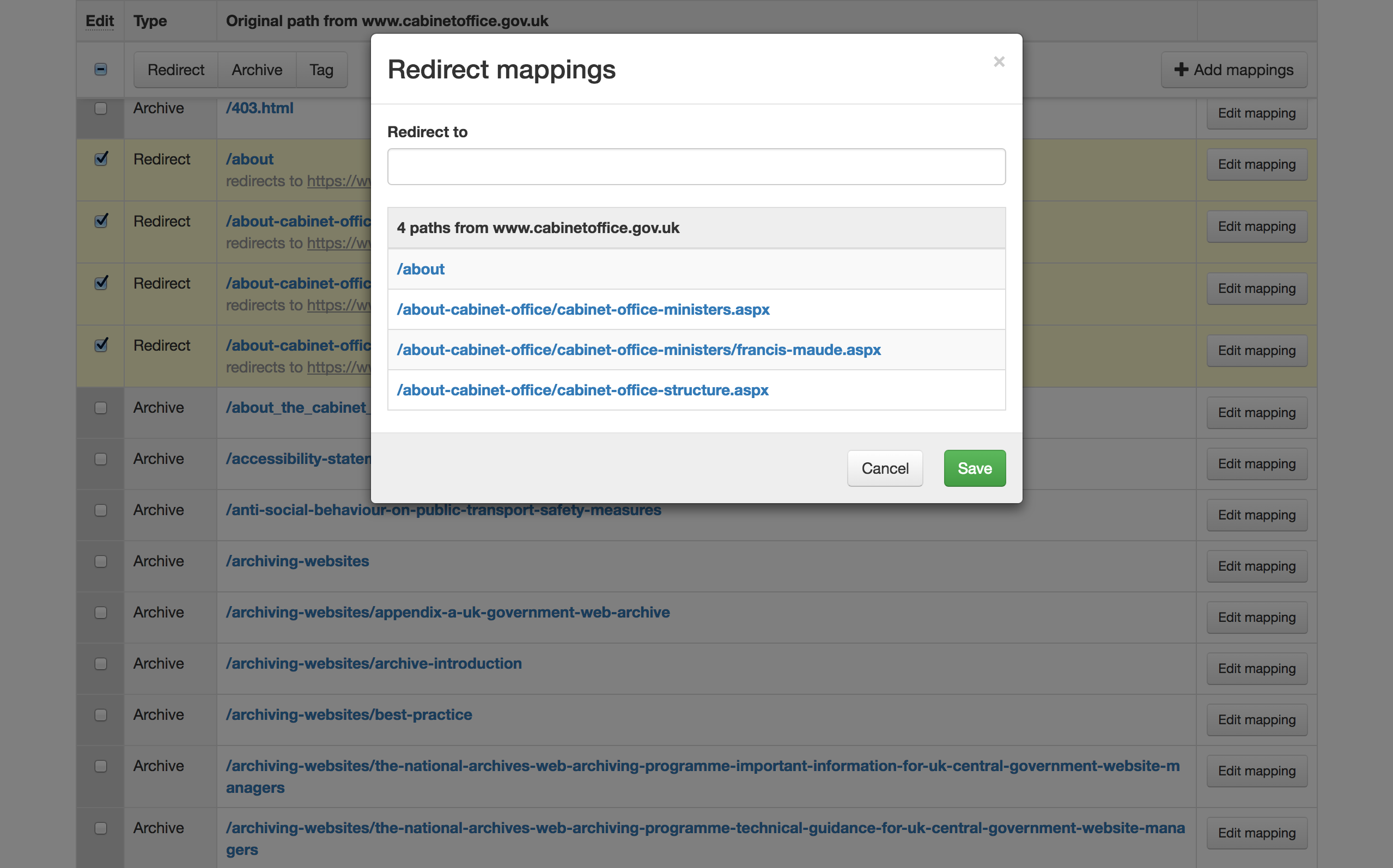

Editing multiple mappings

On a list of mappings we added a way of selecting a range (one by one, or by shift-clicking a range) using a familiar pattern found in web email clients. That set of mappings could then be redirected, archived or tagged. It tested well.

Grouping mappings

To group paths we added filtering and tagging. Organisations were free to create groups of mappings with whatever tags they liked. Tag autocomplete encouraged users to select tags their organisation had already used while tags themselves were hyphenated and lowercased to eliminate a lot of inadvertent variation. This follows my design principle of “Making it hard to do things badly”.

What paths are most important

To indicate which paths had most importance we added hit counts, in a column that could be sorted.

Which paths were ready?

The default mapping was “Archive”, but it wasn’t clear whether a mapping was set to archive through choice or by default. A third pseudo-state was introduced, it behaved exactly like an archive but had the type “Unresolved”, this made it clear which URLs were being archived by default or still required a decision.

Fixing mappings

After transition it’s important to check on the performance of mappings. It’s possible that mappings were missed (they were imported from web logs), or mistakes were made – an archive with a real user need.

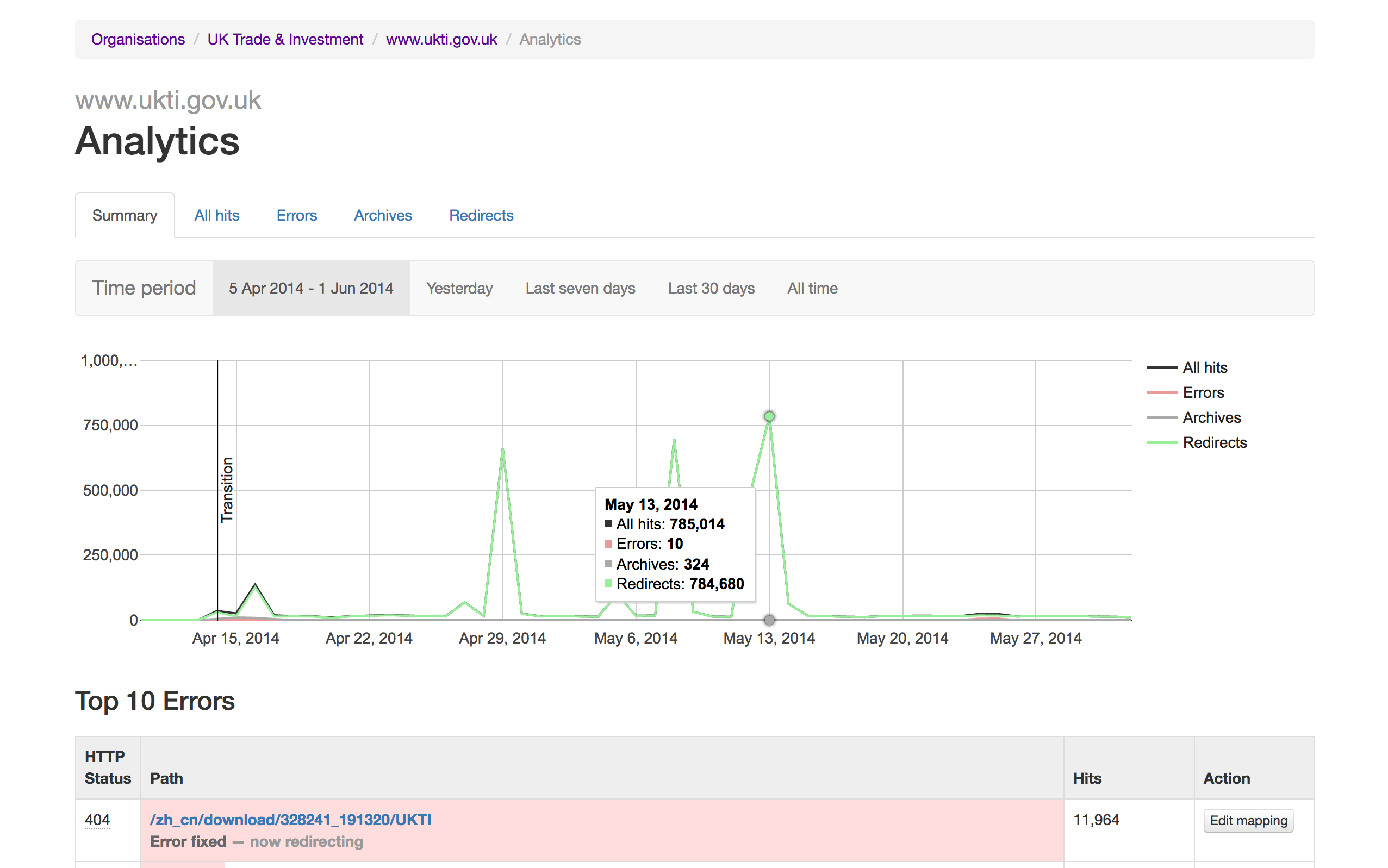

The transition application provides analytics for all old websites, showing which URLs are being hit and what proportion of them are archives, redirects or errors; an error being a 404 page that has no corresponding mapping.

David Mann outlined the process on the transition blog. High traffic to redirects is what’s expected, but many errors would suggest many missing mappings, and high traffic to an archive might indicate a user need that’s been missed.

Based on research findings, we made it easy to:

- create a mapping from an error

- edit any mapping from analytics

- know whether changes had already been made to fix a mapping